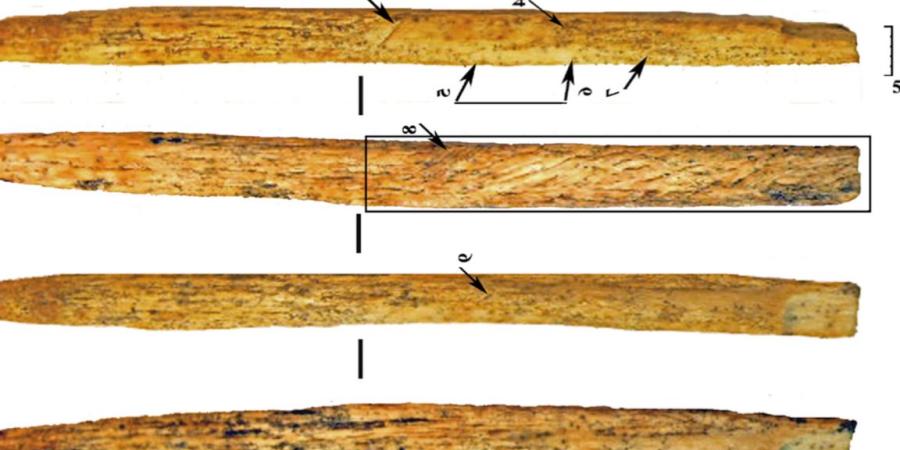

Working bone into a streamlined, aerodynamic spear point, then hafting it onto a shaft with tar that had to be extracted and refined before use takes some sophisticated knowledge and skill. And it’s clear that the Neanderthals developed that skill on their own, instead of acquiring it from our species through some sort of prehistoric ITAR violation. Even so, Golovanova and colleagues note in their paper that “the production technology of bone-tipped hunting weapons used by Neanderthals was in the nascent level in comparison to those used and introduced by modern humans.” (Which seems a bit rude.)

Slightly damaged, use at own risk

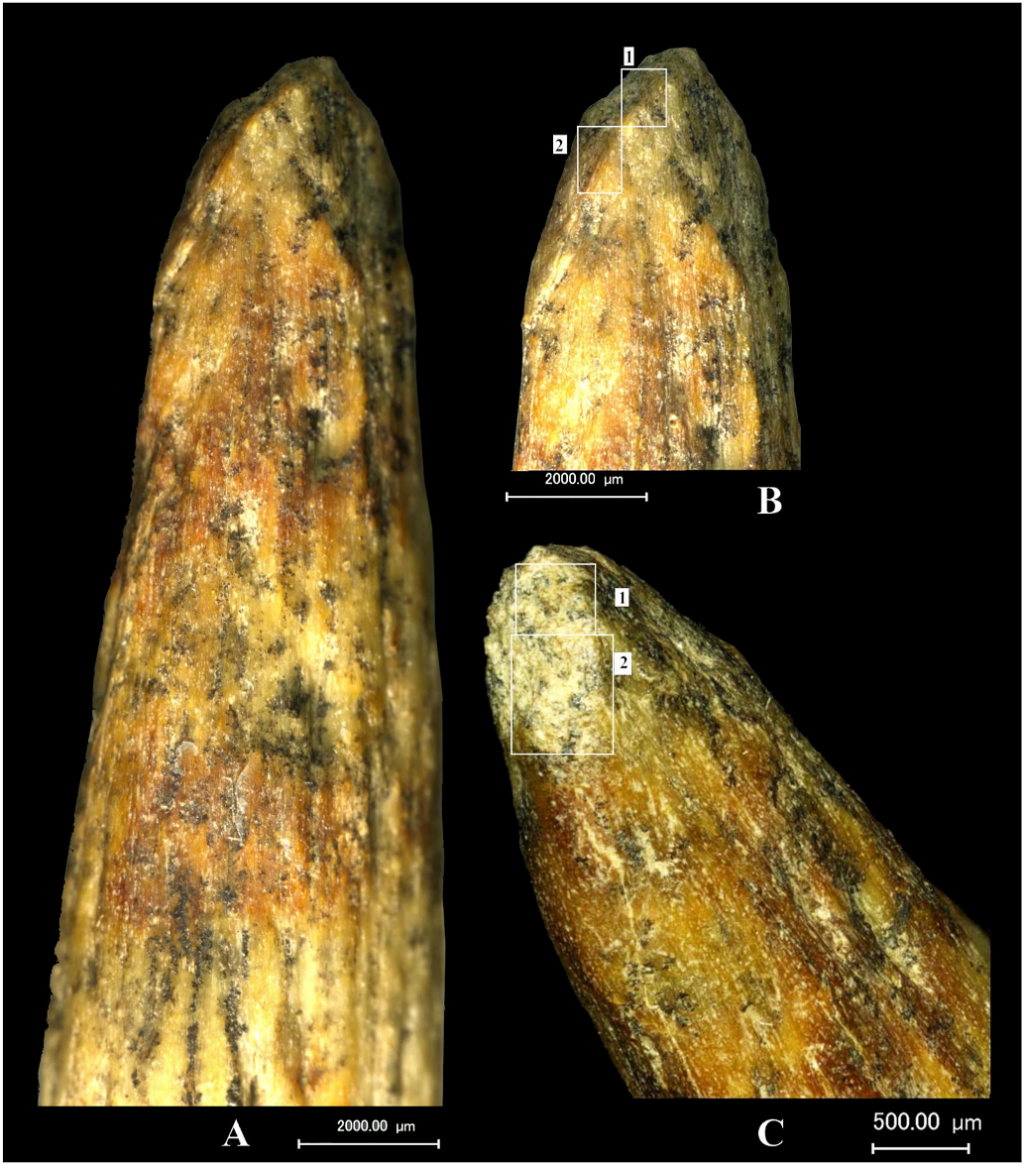

In these magnified photos, you can see the impact damage to the point's tip. Credit: Golovanova et al. 2025

A small crack at the tip of the spear point shows that some Neanderthal hunter used it at least once and managed to hit something. Golovanova and colleagues examined the crack and the finer network of cracks (visible in micro-CT images) that spread back and out from the original break. Those cracks closely resembled damage from a head-on impact, which archaeologists have seen in bone tools from other sites and in experimental studies (also called “archaeologists made some bone-tipped spears and threw them at things to see what would happen,” which is an excellent approach to science).

And apparently a bone spear point was worth trying to fix up and re-use, because traces of grinding show that someone tried to smooth out the crack, probably with a stone tool.

What kinds of prey were the Neanderthals of Mezmaiskaya Cave hunting? Based on the bones found in the cave, many of which show marks from cutting and scraping, the local menu included some birds and small mammals, but also bigger game like bison, deer, relatives of modern horses, and wild sheep and goats.

The point is, interspecies interactions are complicated

Archaeologists have found plenty of evidence that Neanderthals used bone tools for all sorts of things, from shaping and retouching stone to softening animal hides. The projectile point, though, is the first evidence that Neanderthals knew how to carefully work bone into a particular shape, instead of just picking up a conveniently shaped rib to smooth out some hides.

Using specific processes to sculpt bone, combined with using ocher to decorate things and using tar and resin to stick things together, is part of what anthropologists have defined as “modern” human behavior. And it looks like Homo sapiens and Neanderthals each worked most of it out on their own, separately, long before the two species met.

There’s good reason to think that the two groups eventually traded some key bits of technology here and there, but that exchange wasn’t the one-way street that anthropologists once expected.

Journal of Archaeological Science, 2023 DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2025.106223; (About DOIs).

0 تعليق